Philippians 4:4-7 / John 1:19-28

What sayest thou of thyself?

When we want someone to take responsibility, when when we want someone to account for what he is doing, and most especially when what he is doing is not merely out of the ordinary, but seems quite clearly out of bounds or unwarranted, we are accustomed a pointed question: Who do you think you are? Or, perhaps, less direct, but no less pointedly, we ask, What do you have to say for yourself? The idea here is that we take self-definition, self-understanding to be crucial. Who we think we are, what we have to say about ourselves, we hold to be central to assessing whether what we do and how we live is warranted. Consciously or not, we intuit the scholastic dictum agere sequitur esse: action follows being. We intuit, that is, that what things or persons do flows from who or what they are. Since it seems unproblematic that who we think we are is, if not the basis of, then at least central to the kind of person we actually are, then the question is obvious. In the face of puzzling behavior, what better query than, Who do you think you are? What do you have to say for yourself?

It is just this intuition that seems to animate the priests and Levites sent by the Jews of Jerusalem to interrogate John the Baptist. Confronted by his baptisms, and more centrally his preaching of repentance, and even more attending to the large numbers of people heeding his words, they wanted to know just what warrant he thought himself to have to speak and act as he did. Who art thou? they ask. John, however, does not accept their line of questioning. In the face of their repeated request for a positive answer, for saying something of himself, John issues a series of denials: I am not the Christ or I am not. Pressed to the point, pressed to account for himself, that is pressed to speak his own words on his own behalf, John persists in his refusal. He does, to be sure, make a positive claim about his identity: I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness: Make straight the way of the Lord, as said the Prophet Isaias.

Even here, even when John is willing to confess who he understands himself to be, by what warrant he baptizes and preaches, he steadfastly refuses to say anything of himself. His words, the words that disclose who he is, are not his own. They are the words of the prophet Isaiah, which is of course to say, that they are the words of God. It is God, and God alone, whom John allows to define him, to give an account for what he is doing. It is God, and God alone, who authorizes his baptizing and his preaching, for it is to prepare the way for God's coming, and for this purpose alone, that he has been sent. He does not identify himself, he does not say anything of himself, not to be difficult, not as a display of passive aggression, but rather because anything he would say of himself would conceal, rather than reveal the truth. Who he is, as baptizer and preacher, who his is, as witness to the Incarnate Word and Lamb of God, is not of himself, not the product of his own decisions, but a gift, a grace. It is not what he says of himself, but what God says of him through the prophet Isaiah, that constitutes him, that makes John who he is, not merely in his natural self, but all the more as called to eternal life with God himself.

What is true of the Baptist is no less true of those who are baptized in water and the Spirit. We are who we are in Jesus Christ, not because we have made it so. We share in the life of faith not as the product of our own efforts, our own self-definition. Rather, our new life in Christ, our being called to share in the peace of God, which surpasseth all understanding, is a calling, not an accomplishment. To the query Who art thou?, each of us might have a quite different answer to give, but in this we share a common reply with John the Baptist. It is what God has made of us, who God has called us to be, that makes us to be who we are. This is the source of our rejoicing, this is our motive to cast aside all worrying as though our worries and troubles have the final say. We are who who are, and we say of ourselves, simply that we are Christian, and keep our minds and hearts neither on ourselves nor on our troubles, but in the only source of hope and joy and rejoicing, in Christ Jesus our Lord.

How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace, and bring glad tidings of good things!

Sunday, December 14, 2014

Sunday, December 7, 2014

Second Sunday of Advent

Romans 15:4-13 / Matthew 11:2-10

What is it that Jesus Christ came into the world to reveal? We might quite easily answer that he came to reveal God, and God's will for man, and this would surely be correct. The Scriptures, St. Paul tells us, were written for our teaching so that we might have hope. And why hope? That we might with one mind and with one heart we may glorify God and the Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ. When John the Baptist sent two of his disciples to Jesus, it was precisely that he might know who Jesus was, to be certain whether Jesus is in fact the one who is to come, the promised Messiah, or whether he needed to look for another. That is, he looked to Jesus to know just who Jesus is, to find in him, or not, a clear revelation of the saving will of God.

Yet, we find something curious about Jesus' reply. To be sure, Jesus answers John's question. He directs John's disciples to consider what they have seen and heard: the blind see, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead rise again, to poor have the gospel preached to them. The signs are clear and unambiguous, at least for those who already trusted in the words God spoke through his prophets. However, at this point, Jesus turns the question around. He asks the crowd what they looked for in going out to see the John the Baptist. He notes that they cannot have gone to see anything other than one whom they took to be a prophet. Here is where the interesting turn happens. If Jesus is the one whom the signs prove him to be, that is, knowing Jesus to be the promised Christ, then who does this mean that John the Baptist is? He cannot be a mere prophet, as Jesus notes, but more than a prophet, the one of whom it is written: Behold I send my angel before thy face, who shall prepare thy way before thee.

A similar turn happens in Paul's letter to the Romans. Noting that for the Jews, the circumcision in Paul's language, the merciful revelation in Jesus Christ is a reaffirmation of the promises they already held, a reassertion if in a fuller way of a God whom they already knew. Yet, for the Gentiles, the revelation in Christ reveals who they are as well. In Jesus, we find that the Gentiles are, as much as the Jews, part of God's plan all along, that the saving mission for the promised one of Israel is, at the same time, the one in whom the Gentiles shall hope. Despite all appearances, the Gentiles, no less than the Jews, occupy a crucial place in the total plan of God's saving work.

What this suggests is that, in coming to know and confess who God really is, in coming to know God in the Incarnate Word, in Jesus Christ, and in knowing his saving plan for us, we at the same time come to a revelation of ourselves. In seeing who Christ is for us, we see at the same moment who we are meant to be for him, how we have played and continue to play a role in his saving work. This is why Advent is part of why Advent is a time of penance, a time of transformation. Advent summons us to abandon our false selves, to let go of the persons we thought ourselves to be. Advent invites us to enter in hope and joy into the identities God has revealed for us in his merciful coming, whom God has made known in the cave at Bethlehem, on the Cross at Golgotha, in the empty Tomb, and will make known for all to see in his glorious return.

What is it that Jesus Christ came into the world to reveal? We might quite easily answer that he came to reveal God, and God's will for man, and this would surely be correct. The Scriptures, St. Paul tells us, were written for our teaching so that we might have hope. And why hope? That we might with one mind and with one heart we may glorify God and the Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ. When John the Baptist sent two of his disciples to Jesus, it was precisely that he might know who Jesus was, to be certain whether Jesus is in fact the one who is to come, the promised Messiah, or whether he needed to look for another. That is, he looked to Jesus to know just who Jesus is, to find in him, or not, a clear revelation of the saving will of God.

Yet, we find something curious about Jesus' reply. To be sure, Jesus answers John's question. He directs John's disciples to consider what they have seen and heard: the blind see, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead rise again, to poor have the gospel preached to them. The signs are clear and unambiguous, at least for those who already trusted in the words God spoke through his prophets. However, at this point, Jesus turns the question around. He asks the crowd what they looked for in going out to see the John the Baptist. He notes that they cannot have gone to see anything other than one whom they took to be a prophet. Here is where the interesting turn happens. If Jesus is the one whom the signs prove him to be, that is, knowing Jesus to be the promised Christ, then who does this mean that John the Baptist is? He cannot be a mere prophet, as Jesus notes, but more than a prophet, the one of whom it is written: Behold I send my angel before thy face, who shall prepare thy way before thee.

A similar turn happens in Paul's letter to the Romans. Noting that for the Jews, the circumcision in Paul's language, the merciful revelation in Jesus Christ is a reaffirmation of the promises they already held, a reassertion if in a fuller way of a God whom they already knew. Yet, for the Gentiles, the revelation in Christ reveals who they are as well. In Jesus, we find that the Gentiles are, as much as the Jews, part of God's plan all along, that the saving mission for the promised one of Israel is, at the same time, the one in whom the Gentiles shall hope. Despite all appearances, the Gentiles, no less than the Jews, occupy a crucial place in the total plan of God's saving work.

What this suggests is that, in coming to know and confess who God really is, in coming to know God in the Incarnate Word, in Jesus Christ, and in knowing his saving plan for us, we at the same time come to a revelation of ourselves. In seeing who Christ is for us, we see at the same moment who we are meant to be for him, how we have played and continue to play a role in his saving work. This is why Advent is part of why Advent is a time of penance, a time of transformation. Advent summons us to abandon our false selves, to let go of the persons we thought ourselves to be. Advent invites us to enter in hope and joy into the identities God has revealed for us in his merciful coming, whom God has made known in the cave at Bethlehem, on the Cross at Golgotha, in the empty Tomb, and will make known for all to see in his glorious return.

Saturday, December 6, 2014

Saint Nicholas, Bishop and Confessor

Hebrews 13:7-17 / Matthew 25:14-23

There is a hiddenness that is commendable. This is the hiddenness we find in the famous story of St. Nicholas and his liberation of the young women from a life of sexual servitude. In putting the money at the window, or down the chimney, and, as some legends say, into the stockings hung up to dry, while himself endeavoring to remain unseen, unknown, unacknowledged, Nicholas acted rightly. His acts of charity, even as ours, while meant to bind us more deeply to our neighbor, ought even more to direct both us and them to the very source of that charity, to the Lord Jesus Christ, who suffered for us on the Cross with ineffable charity that he might sanctify the people by his own blood. It is this same hiddenness that animates those secret, latter-day helpers of St. Nicholas by filling stockings and shoes across the world with candy, fruit, and presents, that those who receive might be directed not to the earthly minister of these kindly gifts, but to the joy and to him who is the author of all joy.

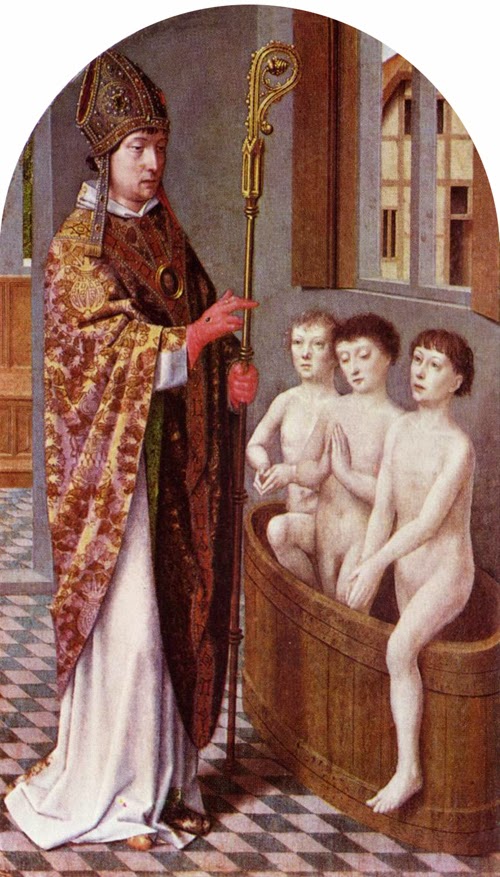

There is another hiddenness that is altogether detestable. This is the hiddenness we find in another story about St. Nicholas, in which the wonder-working bishop, stopping by an inn while on a journey, discerns by supernatural insight that the meat he would be served by the innkeepers is in fact the flesh of three boys, slain by the innkeepers, their bodies picked in a barrel and meant to be provided as food for the guests. This is the hiddenness inherent in all wickedness, the hiddenness that perfers the obscurity of darkness over the manifest glory of the noon-day sun. This is the hiddenness that seeks to plunge not only itself, but all the world, into and unending and unrelenting night of terror rather than turn from its self-inflicted horror and be saved. This is the hiddenness that even today prowls the world, snatching the innocent and helpless, the poor and lonely, and most especially children and the elderly, as its preferred victims. This is, of course, also the hiddenness that cannot escape the penetrating and luminous gaze of the Father of lights, nor the gaze of those filled with his light and truth.

Yet there is another hiddenness which, if less obviously detestable, is nonetheless no better in the long run. This is the hiddenness of those who would shrink back from hope, the hiddenness of the talent placed in the hole dug in the earth by the fearful servant. It is not that the servant did anything positively horrible, but all the same his action, or better yet his inaction, proved ultimately fatal. Why? In seeking to preserve the little he had been given, in acting out of fear rather than hope, in seeing the demand of his master not as the promised assurance of one with confidence in abundant success, but rather a veiled threat of certain failure, the servant prevented himself from entering into the joy of his lord. Said differently, if we do not dare to hope, dare to act in confidence that what God has given us, however little, will and must be abundant in grace, then we have made ourselves to be the kind of people that cannot, that will not be able to enjoy an eternity with God, who have refused to take sure and certain hope in the life-giving power of the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ.

There is a hiddenness that is commendable. This is the hiddenness we find in the famous story of St. Nicholas and his liberation of the young women from a life of sexual servitude. In putting the money at the window, or down the chimney, and, as some legends say, into the stockings hung up to dry, while himself endeavoring to remain unseen, unknown, unacknowledged, Nicholas acted rightly. His acts of charity, even as ours, while meant to bind us more deeply to our neighbor, ought even more to direct both us and them to the very source of that charity, to the Lord Jesus Christ, who suffered for us on the Cross with ineffable charity that he might sanctify the people by his own blood. It is this same hiddenness that animates those secret, latter-day helpers of St. Nicholas by filling stockings and shoes across the world with candy, fruit, and presents, that those who receive might be directed not to the earthly minister of these kindly gifts, but to the joy and to him who is the author of all joy.

There is another hiddenness that is altogether detestable. This is the hiddenness we find in another story about St. Nicholas, in which the wonder-working bishop, stopping by an inn while on a journey, discerns by supernatural insight that the meat he would be served by the innkeepers is in fact the flesh of three boys, slain by the innkeepers, their bodies picked in a barrel and meant to be provided as food for the guests. This is the hiddenness inherent in all wickedness, the hiddenness that perfers the obscurity of darkness over the manifest glory of the noon-day sun. This is the hiddenness that seeks to plunge not only itself, but all the world, into and unending and unrelenting night of terror rather than turn from its self-inflicted horror and be saved. This is the hiddenness that even today prowls the world, snatching the innocent and helpless, the poor and lonely, and most especially children and the elderly, as its preferred victims. This is, of course, also the hiddenness that cannot escape the penetrating and luminous gaze of the Father of lights, nor the gaze of those filled with his light and truth.

Yet there is another hiddenness which, if less obviously detestable, is nonetheless no better in the long run. This is the hiddenness of those who would shrink back from hope, the hiddenness of the talent placed in the hole dug in the earth by the fearful servant. It is not that the servant did anything positively horrible, but all the same his action, or better yet his inaction, proved ultimately fatal. Why? In seeking to preserve the little he had been given, in acting out of fear rather than hope, in seeing the demand of his master not as the promised assurance of one with confidence in abundant success, but rather a veiled threat of certain failure, the servant prevented himself from entering into the joy of his lord. Said differently, if we do not dare to hope, dare to act in confidence that what God has given us, however little, will and must be abundant in grace, then we have made ourselves to be the kind of people that cannot, that will not be able to enjoy an eternity with God, who have refused to take sure and certain hope in the life-giving power of the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Wednesday, December 3, 2014

Saint Francis Xavier, S.J.

Romans 10:10-18 / Mark 16:15-18

...they shall take up serpents; and if they shall drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them...

The missionary journeys of St. Francis Xavier are famous, inspiring, fantastic and, for many, a little too much to believe. Could any one man really convert so many thousands of people, thirty thousand by some estimates? Or, if he brought that number to the font, can we really believe they knew anything of the Christian faith?

It's easy enough to dismiss such numbers as incredible, when we might find it hard to convince even one friend to join us for one week at Mass, much less tens of thousands to come to Christ in baptism, thousands who did not even speak the same language as the one making the appeal. We might be tempted to think this is pious exaggeration, a way of insisting on his heroic sanctity through an inflation of the actual numbers. Although, even then, are we more likely to follow this heroic missionary if we knew the numbers he converted were more "reasonable"? How much fewer did he need to call to faith for us to believe such a thing is even possible? Or, how many need there be, at which point we might imagine that mission for Christ is worth the effort? Had he brought only one person to Jesus Christ, would we then be more willing to share the faith?

If we doubt the witness of Francis Xavier, how much more we must doubt the promises of Jesus Christ to his disciples when he sent them out to the whole world to preach and baptize. If we can lead ourselves to accept the casting out devils, and just might squint at the speaking in tongues to be less outright miracle and more divinely-inspired language training, we are more likely to pause at the claims which follow: snake-handling, immunity to poisons, healing by the laying on of hands.

While it is true that we have no right to expect any specific miraculous intervention in our giving witness to Christ—as the life of St. Paul himself could easily attest—it is just as spiritually dangerous to live as though we cannot hope in doing great things, indeed superhuman, miraculous things, in the service of the Gospel. The promises of Jesus Christ are not to be trifled with, they are not to be dismissed with the condescending wave of our hand. Rather, we might well ask ourselves whether we even believe God might do such things. If not, we might well wonder why we have cast our lot with the man who was born of a Virgin, who healed the sick, who was raised from the dead and ascended into heaven. That is, if we do not live and act not merely as though Jesus could intervene on behalf of the Good News in dramatic ways, but really and truly believing that he might, might this not explain, at least in part, the paltry show we can give of those who have been brought to Christ by our witness?

Advent is a season of hope, a season of renewed confidence in God, who brings light where there was gloom, abundant food where there was want, joy in place of sorrow, life in the shadow of death. Shall we not, this Advent, renew our faith in God who has, still does, and ever will work mighty deeds?

...they shall take up serpents; and if they shall drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them...

The missionary journeys of St. Francis Xavier are famous, inspiring, fantastic and, for many, a little too much to believe. Could any one man really convert so many thousands of people, thirty thousand by some estimates? Or, if he brought that number to the font, can we really believe they knew anything of the Christian faith?

It's easy enough to dismiss such numbers as incredible, when we might find it hard to convince even one friend to join us for one week at Mass, much less tens of thousands to come to Christ in baptism, thousands who did not even speak the same language as the one making the appeal. We might be tempted to think this is pious exaggeration, a way of insisting on his heroic sanctity through an inflation of the actual numbers. Although, even then, are we more likely to follow this heroic missionary if we knew the numbers he converted were more "reasonable"? How much fewer did he need to call to faith for us to believe such a thing is even possible? Or, how many need there be, at which point we might imagine that mission for Christ is worth the effort? Had he brought only one person to Jesus Christ, would we then be more willing to share the faith?

If we doubt the witness of Francis Xavier, how much more we must doubt the promises of Jesus Christ to his disciples when he sent them out to the whole world to preach and baptize. If we can lead ourselves to accept the casting out devils, and just might squint at the speaking in tongues to be less outright miracle and more divinely-inspired language training, we are more likely to pause at the claims which follow: snake-handling, immunity to poisons, healing by the laying on of hands.

While it is true that we have no right to expect any specific miraculous intervention in our giving witness to Christ—as the life of St. Paul himself could easily attest—it is just as spiritually dangerous to live as though we cannot hope in doing great things, indeed superhuman, miraculous things, in the service of the Gospel. The promises of Jesus Christ are not to be trifled with, they are not to be dismissed with the condescending wave of our hand. Rather, we might well ask ourselves whether we even believe God might do such things. If not, we might well wonder why we have cast our lot with the man who was born of a Virgin, who healed the sick, who was raised from the dead and ascended into heaven. That is, if we do not live and act not merely as though Jesus could intervene on behalf of the Good News in dramatic ways, but really and truly believing that he might, might this not explain, at least in part, the paltry show we can give of those who have been brought to Christ by our witness?

Advent is a season of hope, a season of renewed confidence in God, who brings light where there was gloom, abundant food where there was want, joy in place of sorrow, life in the shadow of death. Shall we not, this Advent, renew our faith in God who has, still does, and ever will work mighty deeds?

Tuesday, December 2, 2014

St. Bibiana, Virgin and Martyr

Ecclesiasticus 51:13-17 / Matthew 13:44-52

The Kingdom of heaven is like unto a treasure hidden in a field.

We don't know much for certain of the life of St. Bibiana. Skeptics suggest that everything told of her life was merely concocted to account for the presence of the church now bearing her name in the city of Rome, and etiological myth. Those less cynical must nonetheless admit that our knowledge of the details of her life and martyrdom are, at best, less than certain. One thing that we are assured, however, is that St. Bibiana, like many martyrs before and after her, experienced joy during her martyrdom. First punished with the deprivation of food, then alternately seduced and beaten by a cruel woman, and then finally tied to a column and whipped with scourges tipped with lead, Bibiana yet remained joyful.

Some may worry that these stories of joyful martyrs are cruel, even dangerous. On this worry, they suggest that we should not be moved by the real suffering, indeed the real acts of torture, that continue to be perpetrated before us and in our name. The worry is that, in telling the stories of martyrs joyful in their martyrdom, we become calloused against the brutality—physical, psychological, spiritual—of abuse, comforting ourselves in the thought that it can't really be so terrible, if it would be possible, with enough faith, to endure it with joy.

But, this worry is mistaken, and for two reasons. The first reason is that the joy of the martyrs in their martyrdom is known and accepted to be exceptional, a special grace like the working of miracles. When Jesus Christ himself endured great agony, pain so intense that his sweat came from his body like drops of blood merely in anticipation of his Passion, long before a single hand had touched his sacred and innocent body, we can be under no illusion that we are guaranteed to be spared terrible pains, should they be directed our way. We can hardly expect that a Christian death ought to expect, in the norm, to be exempt from the example of Christ.

The second reason is that the joy of the martyrs in their martyrdom is meant to be a sign of hope. This is not the hope of a kind of spiritual anæsthesia that numbs us against the pains of the world. Rather, it is the hope of a sure and certain knowledge of the presence of God in the lives of the faithful, not merely generically or remotely, but deeply, intimately, like a treasure hidden in a field, a treasure so great that, against all reasonable expectations of those who do not know its value or even its presence, one would sell all she has to obtain it, even when, to outward appearance, the exchange is without sense—a fortune for a seemingly empty field. In the joy of the martyrs, we are awakened to the hope that in our sufferings, which are certain to come, we are not alone. Rather, the one whom we love most, the one who loves us more than we can ever know or tell, is with us in the midst of our sufferings. Indeed, what we want above all in our every searching for happiness, that is God himself, is already present in and to those who love him, not less but even more so in their suffering.

This is why the pains of martyrdom cannot annul joy. This is why Advent can be, and ought to be, penitential and joyful all at once. We must awake ourselves and the world to the joyful news that he who has come, and will come again, is already here in our midst. He has come, and will come, and for those who have received him in faith and love, in already and abidingly present with us. When he whom we love above all things, when he who has loved us with a love beyond all telling from before the foundation of the world, is with us, what pain would not be transformed into joy? What sorrow would not be swallowed up in hope?

The Kingdom of heaven is like unto a treasure hidden in a field.

We don't know much for certain of the life of St. Bibiana. Skeptics suggest that everything told of her life was merely concocted to account for the presence of the church now bearing her name in the city of Rome, and etiological myth. Those less cynical must nonetheless admit that our knowledge of the details of her life and martyrdom are, at best, less than certain. One thing that we are assured, however, is that St. Bibiana, like many martyrs before and after her, experienced joy during her martyrdom. First punished with the deprivation of food, then alternately seduced and beaten by a cruel woman, and then finally tied to a column and whipped with scourges tipped with lead, Bibiana yet remained joyful.

Some may worry that these stories of joyful martyrs are cruel, even dangerous. On this worry, they suggest that we should not be moved by the real suffering, indeed the real acts of torture, that continue to be perpetrated before us and in our name. The worry is that, in telling the stories of martyrs joyful in their martyrdom, we become calloused against the brutality—physical, psychological, spiritual—of abuse, comforting ourselves in the thought that it can't really be so terrible, if it would be possible, with enough faith, to endure it with joy.

But, this worry is mistaken, and for two reasons. The first reason is that the joy of the martyrs in their martyrdom is known and accepted to be exceptional, a special grace like the working of miracles. When Jesus Christ himself endured great agony, pain so intense that his sweat came from his body like drops of blood merely in anticipation of his Passion, long before a single hand had touched his sacred and innocent body, we can be under no illusion that we are guaranteed to be spared terrible pains, should they be directed our way. We can hardly expect that a Christian death ought to expect, in the norm, to be exempt from the example of Christ.

The second reason is that the joy of the martyrs in their martyrdom is meant to be a sign of hope. This is not the hope of a kind of spiritual anæsthesia that numbs us against the pains of the world. Rather, it is the hope of a sure and certain knowledge of the presence of God in the lives of the faithful, not merely generically or remotely, but deeply, intimately, like a treasure hidden in a field, a treasure so great that, against all reasonable expectations of those who do not know its value or even its presence, one would sell all she has to obtain it, even when, to outward appearance, the exchange is without sense—a fortune for a seemingly empty field. In the joy of the martyrs, we are awakened to the hope that in our sufferings, which are certain to come, we are not alone. Rather, the one whom we love most, the one who loves us more than we can ever know or tell, is with us in the midst of our sufferings. Indeed, what we want above all in our every searching for happiness, that is God himself, is already present in and to those who love him, not less but even more so in their suffering.

This is why the pains of martyrdom cannot annul joy. This is why Advent can be, and ought to be, penitential and joyful all at once. We must awake ourselves and the world to the joyful news that he who has come, and will come again, is already here in our midst. He has come, and will come, and for those who have received him in faith and love, in already and abidingly present with us. When he whom we love above all things, when he who has loved us with a love beyond all telling from before the foundation of the world, is with us, what pain would not be transformed into joy? What sorrow would not be swallowed up in hope?

Monday, December 1, 2014

Blessed John of Vercelli, O.P.

Much will be asked of us in the Christian life. Much was asked of Bl. John of Vercelli. From his studies in theology and canon law, John would come to be asked by the Order of Preachers to take up the mantle of leadership, first as prior of the priory in Bologna, then as prior provincial of the province of Lombardy, and finally as Master of the Order, a post he held for nearly twenty years until his death. His gifts as a leader, whose humble witness in visiting the friars across Europe, traveling by foot, caught the eye of the pope, who would come to ask him first to direct the Order to assist in bringing peace to the warring states of Italy, then to serve in the ecumenical council of Lyons and seek the union of the Greek Church in the East with the Latin Church in the West, and then to promote in the Church devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus, all of which he did willingly.

Towards the end of his life, John was once again asked to take up an important task, this time the office of Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, but this title he refused. We might well assume that John had finally had enough, that he was no longer willing to do new and difficult work in the Church. To be fair, there may be something to this. No one can responsibly receive every task or mission he is offered. It is untrue to his own limits and, in the end, unfair as well to the one who asks, who needs someone who can give his full effort to the work at hand.

Even so, there is perhaps more in this late refusal by one who had made himself so much at the disposal of the Order and the Church. We might think that making oneself open to the needs of others is a zero sum game, that we have a finite resource which we must divide between ourselves, others, and God, and our task is seeking to find some kind of balance. However, this view, reasonable as it seems, is mistaken. Our task, which is also, or ought to be our joy, is to give ourselves entirely and without reserve to God. It is in that unhesitating self-donation to Jesus Christ, and only there, that we will find what truly gives us life, what truly opens us up to what best fulfills our time on this earth. More than that, it is only in a life of prayer to the Lord that we will have the true wisdom to see when our service to others flows from the life we have with God, and when it flows from something else: our pride, our delusions of omnicompetence, our need to feel wanted or useful, our fear of being misunderstood in refusing, or many other reasons. When we do not become prompt to see the signs of the Spirit active in the world and in our hearts, we can just as easily refuse a task that would have made us more like Jesus Christ, or take on a task that uselessly burdens our hearts.

In Advent, we are called once again to see the signs in the world, to read what seem to many to be calamities, what might well cause the hearts of others to draw back in fear. We, however, are asked to hold our heads erect, not to be bowed down by what is being asked of us by God. We are called, as was John of Vercelli, to see those signs not as unfamiliar and terrifying, but as the clear and comforting language of a God whom we have come to know well in our daily, humble, and open prayer.

Towards the end of his life, John was once again asked to take up an important task, this time the office of Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, but this title he refused. We might well assume that John had finally had enough, that he was no longer willing to do new and difficult work in the Church. To be fair, there may be something to this. No one can responsibly receive every task or mission he is offered. It is untrue to his own limits and, in the end, unfair as well to the one who asks, who needs someone who can give his full effort to the work at hand.

Even so, there is perhaps more in this late refusal by one who had made himself so much at the disposal of the Order and the Church. We might think that making oneself open to the needs of others is a zero sum game, that we have a finite resource which we must divide between ourselves, others, and God, and our task is seeking to find some kind of balance. However, this view, reasonable as it seems, is mistaken. Our task, which is also, or ought to be our joy, is to give ourselves entirely and without reserve to God. It is in that unhesitating self-donation to Jesus Christ, and only there, that we will find what truly gives us life, what truly opens us up to what best fulfills our time on this earth. More than that, it is only in a life of prayer to the Lord that we will have the true wisdom to see when our service to others flows from the life we have with God, and when it flows from something else: our pride, our delusions of omnicompetence, our need to feel wanted or useful, our fear of being misunderstood in refusing, or many other reasons. When we do not become prompt to see the signs of the Spirit active in the world and in our hearts, we can just as easily refuse a task that would have made us more like Jesus Christ, or take on a task that uselessly burdens our hearts.

In Advent, we are called once again to see the signs in the world, to read what seem to many to be calamities, what might well cause the hearts of others to draw back in fear. We, however, are asked to hold our heads erect, not to be bowed down by what is being asked of us by God. We are called, as was John of Vercelli, to see those signs not as unfamiliar and terrifying, but as the clear and comforting language of a God whom we have come to know well in our daily, humble, and open prayer.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)