Galatians 4:22-31 / John 6:1-15

At the beginning of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Fellowship of the Ring, the wizard Gandalf meets up with his old friend, the hobbit Bilbo. The two had adventured together many years ago, and now Gandalf has returned for the celebration of his friend's "one hundred and eleventieth birthday". Now, even for a hobbit, eleventy-one is old by far, yet Bilbo seemed hardly to have aged a day since the wizard had first seen him so many years before.

The reason for this preternatural vigor, however, was far from wholesome. Indeed, it was nothing other than the One Ring, the tool and source of power of the Enemy of all the Free Peoples, indeed of all goodness, light and hope in Middle Earth. As coming from the Enemy, the Ring had no real power to offer life, no real power to create; it could only manipulate and coerce, and ultimately corrupt, whatever it touched. That is why Bilbo's longevity is not experienced by him as a boon, but rather more of a burden. The Ring had not given him any more life; it had merely taken the life properly given to him by his Creator and distributed it, attenuated it over a longer span of year. As Bilbo himself remarks to Gandalf, Why, I feel all thin, sort of stretched , if you know what I mean: like butter that has been scraped over too much bread. That can't be right. (J.R.R. Tolkien, "A Long Expected Party," The Fellowship of the Ring)

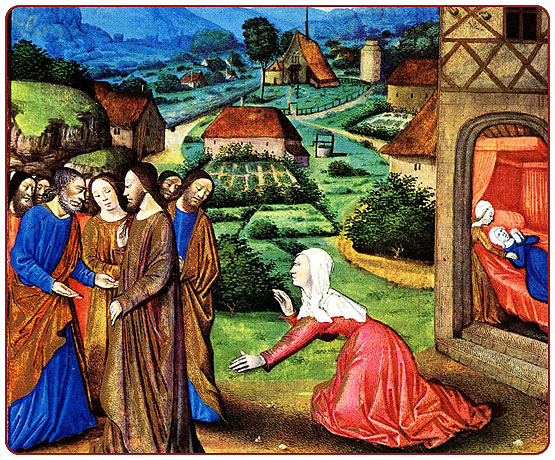

How very different the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves and the fishes at the sea of Galilee. Confronted with limited resources and the real hunger of the very great crowd that had been drawn to Jesus by his signs in the healing of the sick, the disciples were at a loss. Philip, ever practical, knows that a full year's wages would barely be enough to put food in every hungry mouth, and even then each one may receive little. Andrew likewise balks at the sufficiency of their actual resources, five barley loaves and two fishes. But what are these among so many?, he asks, and rightly so. What Philip and Andrew both know, indeed all of the disciples could see and know, is that their resources cannot meet the true and pressing needs of the people. To try to meet the needs of all with the little they had would leave all wanting, the crumbs distributed a mockery of their genuine hunger. To give only to a few, that would be to betray the very mission of their Lord and Christ.

Yet, from their want and need, out of their lack, Jesus produces abundance. From the empty cupboard of their own resources, Jesus calls forth a cornucopia, a horn of plenty, more than they could ever consume. In so doing, Jesus does far more than feed hungry mouths, although he does this indeed. In the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves and fishes, Jesus reveals to us both the radical insufficiency of our own resources, our own fundamental incapacity to achieve what we most need and desire, and his own superabundance as the root and source of all we could ever want and unimaginably more besides.

What is true here in a material way is all the more true in the spiritual life. The Church, like the great crowd at the sea of Galilee, has deep desires, deep needs. It also has many tasks set to it by Christ. While God never assigns a task for which he does not give the graces necessary to accomplish it, nonetheless such grace always remains gift. It always remains something from God, and not from us. Even the Eucharist, the very life of the Church and of each Christian, of which the loaves and fishes were but a sign, comes not from the resources of the gathered community, but only through the word Christ by the power of his Spirit. The priesthood, by whom the Eucharist is offered, is likewise at one and the same time essential to the life of the Church and only ever received as gift from without. It is not through the calling forth of the assembled community, but by the conforming grace and character of Jesus Christ, that the Church has in her heart those sacred ministers by whose ministry she is sanctified and maintained in her life and mission.

This is why prayer and patience are so crucial to the life of the Church, especially in the face of the present needs of so many across the world. If we imagine that we have in ourselves what is needed to supply what the world needs, we will be sadly and tragically mistaken. Like the crowd, we will be trying to seize Jesus and make him serve what we think to be our best interests. Indeed, our attempt to rely on even the graces we have already received will leave us like Bilbo, like butter scraped over too much bread. Rather, it is only in our constant reliance on and waiting for the gracious mercy of God that we will ever have the resources to more than supply our desires. God is abundant; we stand in need. Is there any place else to go, than to him who supplies us with life beyond all measure, with graces past counting?