Isaiah 52:6-10 / Hebrews 1:1-12 / John 1:1-14

God, who at sundry times and in divers manners spoke in times past to the fathers by the prophets, last of all in these days has spoken to us by His Son ...

Why do they gather at the manger, those shepherds of old? Curiosity, perhaps. A humble submission to the word of an angel? Most assuredly. Delight at the song of the heavenly hosts? Perhaps even that, too.

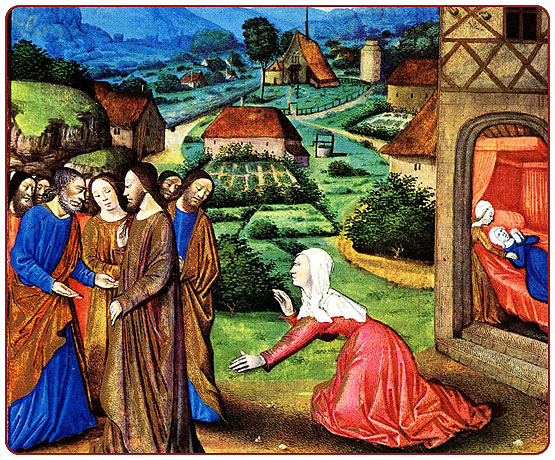

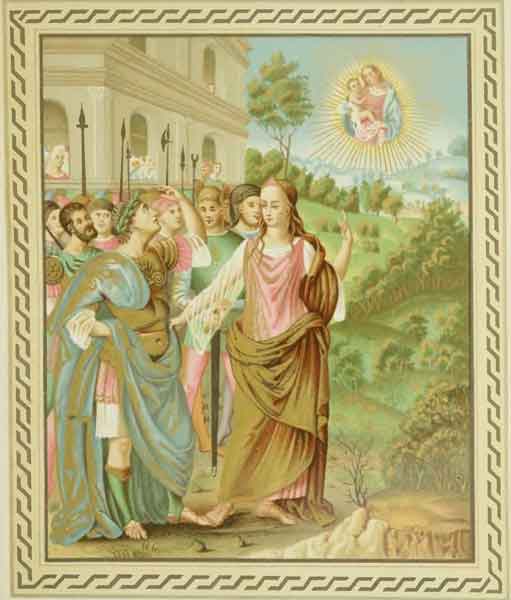

Why do they gather at the manger, those wise men from the East? Are they following their own holy books, seeking to find whole, pure, entire what they find there only in broken and partial ways, alloy of divine truth, the best of human hopes, and empty imaginings, both malevolent and benign? Undoubtedly. Might they also intuit that this star which guides them speaks a truth more than the stars in their cold, unchanging light can ever know, that perhaps the local, specific, even narrow revelation to the long-humbled people of Israel may hold a truth greater than the whole world could contain, now made even more miraculous by its coming in a little cave in Bethlehem? We may never know.

Why do they gather at the manger, those faithful at Church last evening, at midnight, at dawn, and during the day? Have they come with a long-stable and fervent faith, rejoicing in words they know too feeble to celebrate the Word made flesh? Quite certainly, for many this is so. To fulfill an old family custom, as much out of intertia and a worry that Christmas is not Christmas without a dollop of church on the side as of any remnants of lively faith? Because the beauty of the music, the majesty of the words, the poetry of the story itself, if not believed, is at least evocative of meaning, what truth ought to look, sound, even smell like, if only it were so? For these and countless other reasons.

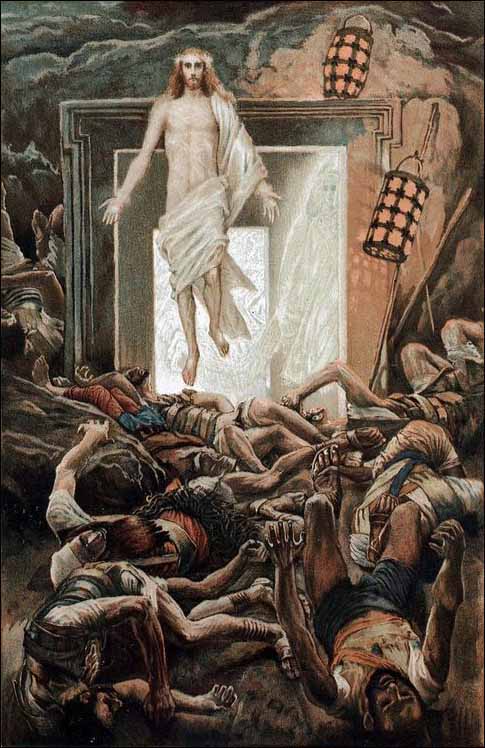

Yet, come they do, and for that we ought not to shake our heads in dismay but instead rejoice in wonder. It should have been altogether easy for the people of promise to recognize his first coming, but He was in the world, and the world was made by Him, and the world knew Him not; He came to his own, and His own received Him not. He was received by many — the lowly and the powerful, shepherds and magi. He was worshiped by all, by the brute beasts and the awesome and terrifying bodiless hosts of heaven, and by the sons of earth as well, the sons and daughters of Adam and Eve whom he had come to save, whose kin he had become, whose lot he had chosen to share. It mattered little what brought them there. What mattered in the cave at Bethlehem was what would matter some thirty years later at another cave in which no one had been laid. What matters is that they saw and believed.

The world holds forth many reasons not to believe: pain, sorrow, a lack of confidence in prophecy or even that the prophets spoke of a future at all. Fine, then, we will speak another way. We will proclaim the Word made flesh with words old and new, and with no words at all. We will appeal to God's prophets to Israel, of course, but if these will not be heard, we will point to the providentially vatic words of those far from the faith. Si non suis vatibus, credat vel gentilibus; Sibyllinis versibus haec praedicta. "If not their own prophets, let them at least believe the Gentiles; in the sibylline verses these things were predicted." And if by the Sibyl, why not also in the Vedas or the stories passed on by elders and medicine men along the banks of the St Lawrence? Scruple not what brings them to the Christ child. Let them come, let them see and believe!

ET VERBUM CARO FACTUM EST, ET HABITAVIT IN NOBIS.